Spring is here again, and you know what that means: love is in the air, roofies are in the drinks, and every music publication from here to Istanbul is busy piecing together its annual “Anniversary of Kurt Cobain’s Death” cover story. No foolin’; April is the one month of the year during which the Barnes and Noble periodical section looks like the family portrait wall at Ma Cobain’s homestead in the Pacific Northwest (provided Ma Cobain adorns her entire living space with nothing but press photos of her late son, which I’m sure she does, just as sure as I am that she actually goes by the namesake “Ma Cobain”). As you read this, there hangs on my wall a ratty old cover of Hit Parader magazine from April 1998 which reads, “FOUR YEARS AFTER HIS DEATH, WE REMEMBER KURT COBAIN,” and features a blurred picture of the former pioneer of Seattle’s supersonic making a fake-angry face and badly in need of a shower. The story advertised by this cover was a four-page Nirvana career retrospective, augmented by a forum for editorial gossip about Courtney Love as well as the usual fodder about Cobain’s personal life (rags-to-riches story, tortured childhood, “was it really a suicide?” etc.), and even independent of the fact that it yielded a totally bitchin’ wall decoration that’s been keeping me company for the past eight years, the article was a decent, if a little dry, rundown of what Nirvana, and indeed Cobain himself, were all about.

Yet annoyingly, though perhaps not unpredictably, Hit Parader and/or any given number of its journalistic contemporaries have been annually publishing this exact same article since about 1995. Never mind that no real legitimate new information regarding Cobain’s life, death, or music ever seems to surface, or that the articles themselves are seldom anything more than ritual recitation of commonly known trivia – the face of a dead rock star on a magazine with the word commemorative written somewhere on the cover is – to borrow a phrase from the man himself – a guaranteed unit shifter, if not necessarily a radio friendly one.

We Americans love our dead rock stars, especially our dead rock stars whose deaths come with an asterisk (suicide, drug overdose, mysterious drowning, shot to death by the hired goons of a rival rapper, etc.), because this gives us the chance to theorize, to formulate wildly unfounded hypotheses, basically to play a real-life version of Clue: Master Detective using nothing but our handy internet search engines and timeworn copies of In Utero. These things, for the most part, are harmless; it generally fosters entertaining if not enriching dialogue to sit around with people who have nothing better to do on a Saturday night and guess how the fourth proper Nirvana album would have sounded, or speculate what music in general would be like in 2006 had Kurt Cobain not whacked himself in 1994.

A good premature rock death also brings out the hyperbole in the best of us, perennially inciting the ridiculous overuse of terms like “genius,” “masterpiece,” and “most important musician of the last ten years,” as well as a handful of opposing-camp critics who cook up such daring terminologies as “overrated” and “only popular because he’s dead” (side note: anyone who refers to a dead rock star as a “martyr” should be required by law to give his or her entire CD collection to a Goodwill store, and subsequently be forced to listen only to Selena albums for the remainder of his or her natural life). To deify a musician who died young is seen as iconic, especially if you’re one who can claim that you were a fan of said musician before he or she died (this really puts you in there with the elite); to denounce a dead musician shows that you’re too sharp for those damned commemorative Hit Parader articles, that you can see through the bullshit, the hype, and evaluate the art for what it really is. A person in the latter category is also the type who might venture a clever statement like, “Death: it’s the best career move there is.”

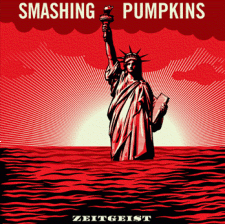

Cobain’s is an odd legacy in that, because he was such a major figurehead in 1990’s pop culture, cynics can (and many do) forever blame the declining state of mainstream rock music on the fact that he’s no longer here to guide us; from context clues, we can deduce that groups like Nickelback and Creed wouldn’t have existed, or at least would have been decidedly better, if Kurt had been around to show them The Way; we can presume that Pearl Jam and the Smashing Pumpkins wouldn’t have “gotten all mellow and shit” if Nirvana were still around to make sure the ante was continually being upped; in general, the public at large can assume it wouldn’t be necessary for groups like The White Stripes and The Vines to feel forced to “save rock” roughly 797 times per year, ’cause if Kurt were here, it totally never woulda died in the first place, man.

Accusatory speculations of this nature do nothing except perpetuate mythology, but that’s okay, because everybody knows that a dead rock star shrouded in myth is a far more interesting case study than a living, breathing rock star who will soon be visiting a theater near you. I would imagine that someone who saw Nirvana in concert is about eighty percent less likely to give a shit about Cobain’s “legacy” than those such as myself and my friends, whose introductions to Nirvana came about thirteen months after Cobain killed himself, at which point there had already been several dozen magazine cover articles dedicated to his deification and idol worship, as well as the seven thousand or so websites generating gossip and spouting conspiracy theories regarding “the truth behind Kurt Cobain’s death.”

Consider my friend Luke who, in eighth grade, had spent weeks worth of after-school hours in our school’s new computer lab researching “the truth”: one of my most absurd (and therefore, one of my fondest) memories of our friendship occurred one evening while Luke was having dinner with our family, during which he spent no less than a half hour explaining to my parents and two little brothers exactly why it was impossible for Kurt Cobain to have committed suicide. While I found it entertaining enough (even though I’d heard the rant tens of times before), the same didn’t necessarily hold true for my brothers, who were five and nine years old, as their usual “So, how was your day at school?” banter was replaced by the clinically certifiable ramblings of an overly enthused adolescent making assertions like, “See, the way his brains were splattered on the greenhouse wall totally shows that, like, he couldn’t have shot himself, because like, the gun was way too big for him to be able to reach the trigger. Kurt was, like, all, uh, short. And stuff.” My parents, they mostly stared on slack-jawed, confused as to who the hell all these people were he kept naming but not curious enough to inquire about it, probably content enough to know that at least Luke now had a hobby besides growing ditch weed in his front yard. My mother in particular excused herself from the table an inordinate number of times that evening, “checking the pot roast” every five minutes or so, more than likely going into the kitchen and contemplating suicide herself.

This was 1996, mind you, when the buzz surrounding the mystery of Cobain’s death was still relatively novel, as the musical tides were starting to turn and self-proclaimed grunge vigilantes were drafting petitions to the Seattle Police Department on their Angelfire sites, calling for a reopening of the Cobain investigation. We would sit in Luke’s upstairs bedroom surfing the net ’round the clock, signing as many of these petitions as could be found by day, downloading super-imposed naked pictures of Alicia Silverstone by night; the times were simple, and while students of the case were unquestionably devoted, it seemed content to remain a hobby of internet wackjobs and thirteen year-old boys who had recently purchased copies of Nevermind and had nothing better to worry about.

But that wasn’t the case. In the following years, there emerged rumors of a massive treasure trove of unreleased Nirvana material that was simply collecting dust in David Geffen’s vaults, just hankering to be released. But wouldn’t you know it, that pesky Courtney Love was at it again! As if her reputation needed additional sullying, here she was trying to prevent the legacy of her husband, the genius, THE MOST CULTURALLY RELEVANT MUSICAL FIGURE OF OUR TIME, from being fully realized. Rolling Stone published news briefs every couple months documenting the status of the increasingly elusive Nirvana rarities box set, but every time they thought they’d pinpointed a release date, along would come Courtney with her team of million dollar lawyers to kick things back another couple of months. This went on for a number of years, yielding nothing until 2002, when Love finally decided it would be okay for the world to at least have a taste of what they’d been missing, in turn allowing Geffen to release the fantastic single “You Know You’re Right” as the bait track on a greatest hits collection. Predictably this only served to whet everyone’s appetite for what may still have been out there, and Love proceeded to drag this out for two more excruciating years. She finally allowed the long-awaited lost tapes of Kurt Cobain to be released in 2004, as a box set titled With the Lights Out (a set of music whose sheer worthlessness I will be complaining about in several minutes here).

Courtney Love, regardless of what you think about her, was (is?) the single most important component to the mythology of Kurt Cobain (and provided she didn’t mind being hated by everyone in the world – and all signs seemed to indicate that she didn’t – she was quite possibly its largest benefactor as well). She was (is?) the antagonist to a protagonist who could no longer fight for himself, which is where we – the internet petition-signers – came in. Every one of Kurt’s mistakes from his drug addiction to the improper way he folded his underpants has at one time or another been blamed extensively on Courtney, because to admit that Cobain was simply an idiot who made a handful of major life fuckups is to demystify his legend, and where’s the fun in that? Of course, it doesn’t hurt that Courtney Love is quite possibly the worst rock and roll wife ever, with only Yoko Ono giving her any real competition. But at least Yoko was only accused of breaking up her husband’s band; Love, on the other hand, was the ideal person to actually blame outright for her husband’s death.

Undoubtedly the circumstances were different, and if John Lennon had committed suicide, Yoko might very well have been prime suspect in the nutjob theories, but Love was just too perfect; she had what could be looked on as a handful of motives, she certainly appeared soulless and cold enough to do it (or at least hire someone to do it, which was the more sensible nonsense proposed by countless speculators), and on top of it all, she was a just a fun person to hate. Sadistic though it may be, Courtney Love is the type of individual whose misfortune you look forward to reading about in People magazine. Conversely, for fans of Nirvana, it was baffling how Kurt Cobain could be so inherently brilliant at music yet so mind-bogglingly stupid at life, so the logical thing to do was to make a him a victim to a conveniently located victimizer. Many Nirvana fans I’ve known have said, “if you were married to Courtney Love, wouldn’t you be addicted to heroin, too?” My answer is invariably yes, I would most certainly turn to smack out of necessity, but then, I’d never marry someone like Courtney Love in the first place, and this immediately becomes where most of us have to stop measuring Cobain by our own yardsticks. He was making shitty decisions long before he married Love; indeed, marrying Love was merely one in a long line of shitty decisions.

For me, the dissolution of the Cobain myth began with Nick Broomfield’s 1998 documentary, Kurt and Courtney, an unfocused attempt at disproving the Cobain suicide report which essentially played like one of the home movies that my friend and I used to make with his dad’s video camera, in which we’d run around outside and conduct interviews with random kids in the neighborhood. What I learned from this movie is that nothing flattens a conspiracy theory like listening to the inane ramblings of someone who actually believes it. Kurt and Courtney was effective in eliciting a nice sympathy trip for Cobain and doing a definite bang-up job of painting Love as a self-serving queen bitch, but didn’t do much for approaching a legitimate, factual case for Cobain’s death being a possible murder rather than a suicide. The most plausible argument presented, one initially instigated by private investigator Tom Grant – that it would have been impossible to have ingested as much heroin as was found in Cobain’s system and still have been coherent enough to discharge a gun – was immediately shot down by a doctor. Broomfield meant well, but everyone with whom I watched this film left the room shaking their heads, and most of us were only eighteen years old. Perhaps there were elements of cynicism in this reaction, but mainly the whole thing just felt like an episode of Jerry Springer with really, really tragic surrounding circumstances (not that any standard episode of Jerry Springer could be described as anything other than “really, really tragic,” but you get the point).

Tearing even further away at the mask was the 2004 release of With the Lights Out, the long-awaited three-CD, one-DVD box set of unreleased recordings, alternate takes, and demos. It hit stores the same day as U2’s How to Dismantle an Atomic Bomb, and indeed, there wasn’t a single track on the entire Nirvana set as memorable as How to Dismantle an Atomic Bomb’s worst song (no small feat considering the four hours worth of material in the Nirvana box). What was originally hailed as a collection of overlooked masterpieces ultimately ended up being a pile of crappy demos and shoddy live performances, items which might be novel for collectors and aficionados to bootleg and trade on the internet, but are borderline criminal to professionally package and market as a legitimate music release. Truly, if Universal scraped the bottom of the barrel any harder to assemble this material, they would have been chipping wood; With the Lights Out, and moreover the entire myth of the Kurt Cobain’s buried treasure, was the biggest music industry sham of my generation, $45.99 that could have been spent on milkshakes and hookers but instead went towards a dozen Nevermind demos that sound like they were recorded over the phone with one of those Talkboy recorders that Macaulay Culkin had in Home Alone 2: Lost in New York.

Nonetheless, the mythbusters had the week off; With the Lights Out was released to mostly enthusiastic reviews, likely written primarily by watery-mouthed fans of the group just so excited to be hearing Kurt Cobain’s voice in an unfamiliar setting that they would have heaped equally hyperbolic praise upon a book-on-tape version Anne of Green Gables as narrated by the man himself.

Consider the first track on the box set, a version of Led Zeppelin’s “Heartbreaker” recorded at a house party in 1987. The recording quality is barely passable, Cobain forgets half the words, and he incoherently yowls his way through the half that he does remember. It is, by and large, a worthless recording. But you can’t really believe that, can you, not unless you spent your life living under the proverbial “rock” under which it is always suggested that ignorant people reside? No, what it is, you blasphemous nay-saying sodomite, is an “early glimpse at Cobain’s genius to come,” or, “a blueprint for the sound that would later come full circle on Bleach.” Some people will grant you that it’s just a bunch of drunk buffoons in a basement having a good time, but it’s rare that there isn’t some sort of false significance attached to even that. Similarly will people insist that a hissy version of “All Apologies” that sounds like it was recorded in the shower with an unamplified electric guitar is not merely a “pile of shit” but rather a “unique insight into the creative process,” meaning that we see answered before our very ears the perpetually baffling question of, “Does a song sound better recorded in a studio with actual recording equipment, or in a bedroom with a cassetteophone with dying batteries?” And there’s a question whose answer is worth $45.99 plus tax, eh?

When dealing with dead rock stars, it’s counterproductive in deciphering the enigmas surrounding them as people if we allow ourselves to view any element of their career as unrevealing, and since nothing is ever enough, we’re constantly on the prowl for missing pieces, information either factual or musical to fill in the gaps. This is why roughly every significant concert Jimi Hendrix or Jeff Buckley ever played is now available on CD, and likewise why everything Tupac Shakur ever uttered in a recording studio has been unvaulted, divvied up, and used as feature spots on the albums of rappers who didn’t even have careers while Shakur was still alive – well, that and money, of course, but it’s our curiosity that engenders the demand. Nirvana’s demos and outtakes aren’t even like those of Bob Dylan or Elvis Costello, where the alternate versions present the songs in a vastly different light and therefore really do shed light on the creative process; almost without exception, Nirvana’s “alternate versions” are really just “unfinished versions.” For a fan to find them interesting is understandable; to presume that they have any degree of significance is to wildly extrapolate.

The one thing With the Lights Out did reveal about Cobain, or at least about his producers, was that he was a brilliant practitioner of quality control. Nowhere in Nirvana’s catalog is there a case of “well, this song should have been included on this album, where this song should have been left off.” Disappointingly, With the Lights Out proved that there are only four truly great Nirvana songs that were not originally released on one of their proper albums: “Even in His Youth,” the B-side to “Smells Like Teen Spirit”; “Verse Chorus Verse,” the unlisted track on the 1993 No Alternative compilation; “I Hate Myself and Want to Die,” from 1993’s The Beavis and Butt-Head Experience; and “You Know You’re Right,” a single recorded early in 1994, released on the self-titled 2002 best of collection. It’s also telling of Courtney Love’s quality-control-o-meter, as well as those of the two surviving members of Nirvana, that none of these four songs appeared on the box set in their definitive versions.

So what of all this folklore? How much of it is legit, and how much is completely unfounded horseshit? Well, since this is a music publication, and since it is indeed spring, I’d be remiss if I didn’t at least so much as attempt to answer the questions that the rock media has been trying to answer for years, partially because they’re cornerstones for good discussion and insightful analysis of what actually does exist, but mainly it’s just fun to speculate (plus I know you’ve all been dying to hear what I have to say about the subject, seeing how this piece isn’t nearly long enough as it is).

Had Kurt Cobain lived to see 1995, what would the fourth proper Nirvana album have sounded like?

Well, a handful of interviews and biographies suggest that the group were on the verge of imploding as it was, so chances are there might never have been a fourth proper Nirvana album at all. But for the sake of debate, and assuming Cobain would have continued on solo ventures even in the absence of his band, I’ve always fancied the notion that Nirvana V 4.0 would have sounded like a sloppy version of R.E.M.’s Automatic for the People, the then-latest record by a band that Cobain loved, and supposedly the record that was playing on the stereo when Cobain’s body was found (a detail presented to us courtesy of Christopher Cross’s biography Heavier than Heaven, which dedicates an entire section to the day of Cobain’s suicide, fabricating details about the event as though he were writing a series of stage directions). Though “You Know You’re Right” suggests otherwise; it’s got as catchy of a chorus as you’ll find anywhere in the Nirvana canon, but its outro boasts an onslaught of cacophonous noise that you can’t find anywhere outside of an amateur Stomp audition. So maybe it would have sounded like “Man on the Moon” played with garbage can lids. If that’s the case, it’s a shame we’ll never get to hear it.

What would music be like in 2006 had Kurt Cobain not whacked himself in 1994?

Probably still awful. Kurt Cobain was no kind of tour guide; he was simply a doorman. “Smells Like Teen Spirit” was a trailblazer, opening the floodgates for countless rock bands to do what they do and expect to have a fair chance at being accepted commercially. But when you’ve extended an open invitation, you can’t expect the riff-raff to simply stay out on principle. Bearing this in mind, groups like Nickelback and Creed don’t exist in the absence of Nirvana, they exist because of them. It doesn’t seem uncommon for music to devalue once it’s been revolutionized; much as the Led Zeppelins and Black Sabbaths of the 1970’s devolved into the Whitesnakes and Ratts of the 1980s, likewise did the Nirvanas and Pearl Jams of the 1990s devolve into the Creeds and Nickelbacks of the new millennium. And that’s not a nostalgic, “the old stuff is better” rant; it’s just a simple matter of breaking down formulas. Groups founded on originality – or more accurately, musical personality types founded on originality – will always outshine their successors because they are, for better or worse, original, and their followers will be trying to create from a formula the same thing that its innovators likely created out of natural inclination. Unless a successor can bring something unique in terms of character to the music from which his or her own is derived, what will likely turn up is a pallid imitation.

Is Kurt Cobain only regarded as highly as he is because he’s dead?

Though I’m sure the pages of endless yammering which preceded this statement may suggest otherwise – no. The music Kurt Cobain left us with is largely the work of a great pop music innovator who was constantly evolving and challenging himself. Nevermind and In Utero would probably still be regarded as fantastic albums if Cobain were still alive – Nevermind for being the groundbreaking pop album that it was, and In Utero for being the respectably challenging but naturally forward-pushing follow-up – even if (especially if?) everything else he’d released since had been utter crap. Both albums peaked at number one on the Billboard charts, and while this alone certainly does not justify the celebration of greatness (the album which Nevermind knocked out of the number one slot was Michael Jackson’s Dangerous – “Heal the World,” indeed), there’s no denying the immense popularity surrounding this music prior to Cobain’s death. The suicide perpetuated the mythology, and will likely hold an immense bearing on any posthumous work which surfaces in the future, but the material that was released during Cobain’s lifetime was mostly given its canonical evaluation well before April 8, 1994. The two remaining studio records – Bleach (1989 Sub Pop debut) and Incesticide (collection of odds and ends and indie singles – who knew, the real version of With the Lights Out was released in 1992, and even then any hype it generated was of questionable foundation) – are both solid if unspectacular releases, essential for an admirer of the group but probably forgettable to casual music fans. Bleach was Cobain before he hit his stride as a songwriter, though great songs are not completely elusive. Incesticide is, on the whole, a lot of dicking around, though in many ways it’s far more accomplished than Bleach; the pop songs are stickier, and the moments of reckless abandon are looser and more ridiculous.

However, the MTV Unplugged in New York album is nothing short of indispensable, primarily for its display of the intricacies and depths of Cobain’s songwriting, which on occasion can be lost beneath the fuzz and crunch of the studio records. There’s a commonplace statement in many discussions in which a song’s merits as a written piece of music are being weighed: “Well, how well does it hold up if you play it on just an acoustic guitar?” Unplugged is the evidence. It’s also the closest we ever got to Kurt Cobain the person; where Nirvana’s studio recordings are often monstrous walls of sound, Unplugged conversely sounds like Kurt sitting on your couch playing you his songs over Sunday tea and biscuits. In other live performances, Kurt was constantly jumping around onstage, possibly in lingerie, sometimes laying on the floor with his guitar and performing a bizarre clockwise running motion; on Unplugged, he was relaxed, seated, and wearing a nice beige sweater that looks like it came from your Uncle Dennis’s yard sale. Me, I always liked it (the album, not the sweater, though now that the subject has been breached I’ll confess to loving the latter almost twice as much) because songs like “Plateau” and “Lake of Fire” were downright hilarious, and while humor was always present in Cobain’s songs, there was something less distant about where it was coming from on the Unplugged record. It was more direct and less ironic, more human and less mythological. Unplugged in New York was the least mythological thing Kurt Cobain ever did; perhaps it only served to proliferate it that he followed it by shooting himself in the face, which remains the most mythological thing he ever did.

There is a moment during the MTV Unplugged broadcast, the break during the last verse of “Where Did You Sleep Last Night,” in which Kurt Cobain opens his eyes, which had been closed for the entire song leading up to this point, and makes what my friends and I used to call the “I’m gonna kill myself” face. It was, at a time, the scariest, most foreboding look I’d ever seen on the visage of another human being; watching it now, as an adult, it looks like he was merely looking out on something that happened in the audience, or possibly taking a breath after screaming the holy hell out of the song’s last verse. Whatever the cause, my friends and my original interpretation of that face was, in addition to being young and generally prone to making up random bullshit, the absolute embodiment of the Cobain legend, the inability to allow one glance to go by without burdening it with some kind of interpretive significance. Perhaps that’s just the lore talking, or maybe it’s just indicative of a great artist in general; whatever it is, it’s a fascination that isn’t going to die anytime soon, especially not with blathering articles like this being written every spring. But then, that’s good mythology for you, inasmuch as every attempt to debunk it only further perpetuates it. That’s all right, though; despite what he declared time and time again, Kurt loved his attention, and I can’t imagine he would have his legend any other way.